Supply chains may never be the same again, but new problems are bound to arise

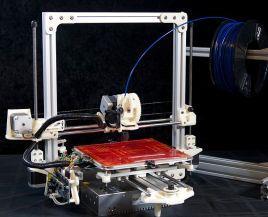

It is undeniable that 3D printing, or additive manufacturing, as it is otherwise known, promises to revolutionise large swathes of traditional product manufacturing and parallels can be drawn between the limited ways in which the internet and email were used in commerce a mere 20 years ago with their near-ubiquity today.

Barely a day goes by without a story being published about a new application for a 3D-printed product or an announcement about a newer, more powerful or quicker printer.

The advocates of 3D printing often talk of the end of the traditional supply chain given that, instead of producing a product in a factory, packaging, shipping, storing it and then getting it to the end-user, the customer can simply download the specifications and print the product on site in whatever numbers it wants.

However, for whatever will be gained in the shrinking of the supply chain, new problems associated with the new technological processes will surely also arise. For instance, a product may be designed by company A, using software produced by company B, printed by company C, on a printer manufactured by company D, which operates software produced by company E, using a polymer produced by company F.

A problem could arise at any stage, and the more numerous the stages, the more likely it is that something will go wrong at some point.

Depending on the product, the consequences of a failure can be extremely serious. Consider the following example: at the beginning of the year, BAE Systems announced that it would be using 3D-printing technology to design and produce parts for its aeroplanes. This would cut the Royal Air Force’s maintenance and service bill by millions. Let us assume hypothetically, that, on a routine test flight, one of these manufactured parts failed, damaging the aircraft and then resulting in investigation into the cause of the accident.

Conceivably, any of the companies A to F mentioned above could be liable for the parts failure.

The issue then is that some of the entities that were involved with printing the parts will have some form of insurance cover, but others will not. Furthermore, some will have used disclaimers in their terms and conditions to try and exclude liability, and some might be in a different jurisdiction from where the accident occurred. Such a situation will inevitably give rise to incredibly complex and costly legal disputes.

To date, there have been no reported instances of such liability issues from 3-D printing. However, the growth of the industry and the fact that it is producing increasingly complex materials, including heart valves for use in surgery and, at the other end of the spectrum perhaps, weaponry, mean that, inevitably, there will be.

However, businesses involved in any aspect of the 3D-printing process can take steps to protect themselves. Producers in the supply chain might want to consider the availability and scope of their insurance cover. It would be prudent to check whether third-party liability can be excluded in standard terms and conditions, or if warnings can be placed on the product and in the instructions for use.

Insurers, on the other hand, ought to consider conditions and exclusions in their policy wordings and what questions they might want to ask when deciding whether to issue cover to an insured.

Ultimately, it is essential not to wait for something to go wrong, but be prepared and to plan for any outcome.

Andrew Stevenson is a partner at Elborne Mitchell

No comments yet