Laws relating to directors' liability vary across Europe - while the spectre of US extradition looms in the background, writes Neil Hodge

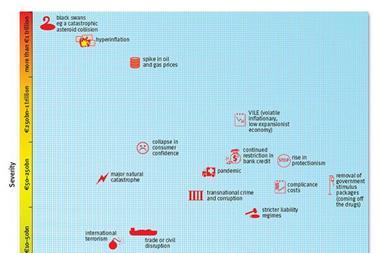

With the European Commission examining whether there should be an easier way for consumers to seek redress from companies for everything from poor corporate governance to faulty products, the issue of directors and officers’ (D&O) insurance has been thrust into the spotlight. And given the myriad of European directives that have been transposed into 27 varieties in each European Union (EU) member state to sit alongside their own existing legislation and regulatory principles, it is little wonder that directors want greater assurance that they are being covered for all risks in their D&O policies, and that the limits of cover are appropriate.

The variations in the levels of cover and indemnity across the EU can be striking. French company law, for example, prohibits clauses limiting or excluding the directors’ liability to the corporation and there is no specific law regarding D&O there. In Spain, the Netherlands and Sweden, on the other hand, indemnification is legally viable if an individual’s liability arises out of fault or negligence, but not fraud, malice or wilful misconduct. And under Hungarian law – as is thought to be the case for the majority of EU member states from the former eastern bloc – D&O insurance is not prohibited: however, it cannot be considered as being generally wide-spread, or even sufficient, as existing case law is sparse.

Consequently, says Christian Wells, partner in the insurance and reinsurance group at law firm Lovells, companies may be at risk of having gaps in their worldwide umbrella D&O coverage, or of paying for cover they cannot use because of differences between jurisdictions. “Some states will not allow companies to indemnify directors, while others may impose duties on the role and responsibilities of directors not covered by a standard wording,” says Wells. “As a result, there is a danger that companies simply buy a panoply of covers in an effort to insure themselves against D&O risk but do not check carefully enough that they are appropriate to the needs of the company, the board, or the local legislation,” he explains.

Under the UK Companies Act there is no restriction on a company’s power to provide D&O cover for their directors and other officers. And boards are thankful for it. Legislation such as the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, the Company Directors Disqualification Act 1986, the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, the Enterprise Act 2002, the Companies Act 2006, and the Environmental Damage Regulations 2009 all add to the duties – and burden – that directors need to take into account and take insurance against.

Higher defence costs

But directors in the UK may feel at greater risk due to the government’s attempts to cut legal aid costs. Under changes that came into effect as of 31 October 2009, companies and directors cleared of criminal charges are now barred from recovering their defence costs to curb taxpayer-funded legal spending. Lawyers warn that the changes could leave businesses and individuals acquitted of fraud, corporate manslaughter and other serious offences with bills ranging up to several million pounds.

Under the previous system, defendants found not guilty of criminal charges were compensated for “reasonable” legal defence costs. But the Ministry of Justice complained that public legal spending was vulnerable to high cost, one-off cases where privately funded defendants, often in circumstances where a company has been accused of a criminal offence, were acquitted. For example, engineering firm Balfour Beatty and UK rail infrastructure firm Network Rail recovered £21m in legal costs from the government’s central funds pool after being cleared of manslaughter charges in connection with the 2000 Hatfield rail crash, despite being fined a combined £11m for related health and safety failings.

Jonathan Grimes, a member of the London Solicitors Litigation Association (LSLA), an organisation that represents the interests of a wide range of civil litigators in London, and a solicitor at Kingsley Napley, says that the changes are likely to mean that companies will bear greater costs. “These changes mean that it is likely that there will be an effect on the cover that insurers are willing to offer and the cost of that cover since insurers will no longer be able to recover if their insured is acquitted or the case discontinued,” he says.

Some experts have also warned that some companies may be in danger of creating a “two-tier” D&O policy for their boards, affording greater levels of life-time cover to executives and only providing non-executives with cover during their tenure. Jonathan Corman, partner in the business and professional risks group at solicitors Browne Jacobson, says that “executive directors may be covered for a lengthy period after they leave the company, even up to their death. However, non-executives – whose term with the company is usually shorter – are not always afforded the same level of protection under the D&O policy and so may be at risk.”

“Non-executives are being pressured to be more challenging in the boardroom and have been singled out by some as being the ‘weak link’ in corporate governance for not objecting to the board’s strategies. As a result, they want the same level of protection as other board members, particularly as there is no legal distinction in UK law between an ‘executive’ director and a ‘non-executive’,” says Corman.

German directors contribute

While the UK is becoming more “risk aware” due to the muscle flexing of industry regulators, directors in other EU member states are also beginning to feel the heat. Germany, which is already well-regarded as a country with a good record of enforcement, has recently passed legislation which will compel directors on management boards (as opposed to supervisory boards) to pay towards their deductibles.

The new Act on the Adequacy of Managerial Salaries was passed on 18 June 2009 and requires listed companies purchasing D&O insurance to impose a personal deductible of at least 10% of each loss, subject to an absolute annual cap which must be set at not less than one and a half times the annual fixed remuneration of the director. The aggregate cap is to be reviewed annually to reflect movements in the fixed element of the director's remuneration. The requirements are to be applicable to all stock corporations, whether in fact listed or privately owned, and will apply with immediate effect to all newly concluded D&O insurance contracts, while those already in existence are to be amended with effect from 1 July 2010 at the latest.

Many have been critical of the move. Hartmut Mai, global head of financial lines at Allianz Global Corporate Specialty, says that “ahead of the country’s election, the German government wanted to be seen to have a draconian response to tackle a perceived problem of directors taking a lax approach to corporate governance. As a result, it has devised a new law which is badly defined, highly unnecessary, very discriminatory, and which is creating a lot of confusion. Laws against directors are already well enforced in Germany and so this is just an added burden. Overseas firms with listings or subsidiaries here are going to find these new rules very tough to understand.”

US threat

However, many experts believe that the real threat to directors and companies is outside of Europe, despite the Commission’s apparent willingness to push collective address. Insurers and lawyers say that US regulators such as the Department of Justice and the Securities and Exchange Commission, as well as US investors, are the most likely to seek compensation and damages awards, and are equally as likely to seek punitive action taken against directors, now under increased threat of extradition due to a new agreement made this year.

On 28 October the US and EU signed an extradition agreement that will update the existing bilateral extradition treaties with each of the member states, in many cases replacing lists of offences that are deemed extraditable with a dual criminality standard. The mutual legal assistance agreement contains provisions that allow the US and EU to increase cooperation, as well as gain access to a subject’s bank accounts and allow any data acquired via the agreement to be used to help extradite that person for an additional serious offence other than just the one triggering the initial request. The EU already has an inter-EU extradition agreement: since 2005 under the European Arrest Warrant, directors can be extradited to any other EU member state to face charges.

The latest agreement largely mirrors the existing US-UK Extradition Treaty, which was ratified in 2007 and which has been criticised as being unfair. Under the Treaty, UK citizens are no longer entitled to legal aid for their defence costs when extradited. One lawyer who asked not to be named said: “This is a very unfair piece of legislation that suits the US and its enforcement agencies a lot more than it does the UK. Any move to extradite UK directors to the US would probably give them the fright of their lives.”

Doug Robare, D&O manager for Zurich Global Corporate in the UK, says that the majority of D&O policies for major European corporates will automatically include cover for US extradition risk. However, he warns that companies need to examine whether they have the appropriate level of cover to meet potential legal costs. “These cases can drag on for years and if a board of say, ten directors, has been extradited to the US during the case, then legal and other associated costs are going to be high. It will be little comfort to win the case but be left with a multi-million dollar legal bill to pick up at the end of it all,” says Robare.

Postscript

Neil Hodge is a freelance writer

No comments yet