Anyone looking to put money into the Bric should not be fooled into thinking the risks are the same. Peter Davy looks at the prospects for Brazil, Russia, India and China.

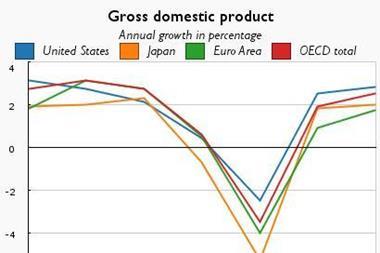

If the attractions of the Bric countries weren’t already clear for businesses before the recession, the financial crisis has done much to highlight them. Not only did three of the big four avoid significant recessions (with China and India growing 8.7 and 6.1 per cent, respectively and Brazil’s GDP shrinking just 0.2 per cent), but the contrast going forward is also stark. The UK’s GDP growth is expected to be 1.0 to 1.5 per cent this year; the IMF reckons China’s will be 9.5 per cent. India’s will be eight per cent. In Brazil, which has rarely seen the stratospheric growth of some emerging markets in recent years, the central bank is predicting 5.8 per cent.

And Brazil also points to another factor in these countries’ favour. This year’s elections will see President Lula da Silva ineligible to run. However, unlike the contest in 2002, against the backdrop of fears of a swing towards socialism, there’s little concern. Much of the optimism around growth this year is down to increased government spending designed to see Lula’s chosen successor, Dilma Rousseff, voted in, but neither she, nor her opponent Jose Serra, are considered much of a risk.

“Business is fairly sanguine about both of the main candidates,” says Jill Hedges, senior editor for Latin America at analysts Oxford Analytica. “We're not likely to see a huge change in economic policy.”

It’s illustrative of a trend across the big emerging markets. In the early stages of the crisis, the fear was that a harsher economic climate would lead to an upsurge in protectionism in the developing world, and a rejection of globalisation. By and large, though, it has failed to materialise – in fact, in some cases, quite the opposite.

Take India, for example. The drive is towards opening up sectors to foreign investment, with the insurance sector targeted for the current year, while the bidding process for infrastructure contracts has already been streamlined to encourage foreign investment. In China, meanwhile, Xianfang Ren in the Beijing office of consultants IHS Global Insight says deregulation is slow, but has seen no reverse; in fact, further moves to open up the oil industry and railways are expected in coming months.

“The government still regards the deregulation as part of the longer term structural adjustment that’s needed to increase productivity,” she says.

Even in Russia, some argue that the decline in the oil price and problems in attracting investments for big new projects have brought a realisation that the country needs foreign capital and technology.

“There’s a softening of attitudes towards foreign investment,” says Michael Denison, research director at Control Risks Group. You can see it in the tax breaks introduced in the oil sector recently. “The days of extremely generous contracts to foreign companies may be over, but there is a willingness now to work with them – albeit on Russian terms.”

The progress towards open markets is so well advanced, it seems, that it is difficult to see it turning back.

And that points to another reason why companies keen to seek out new sources of growth are likely to consider the Brics: others have gone before them. In Brazil, for example, Deutsche Bank celebrates its centenary this year.

Robert McKellar is director of consultancy Harmattan Associates and author of A Short Guide to Political Risk¸ published later this year by Gower. Much of his work is in frontier markets – countries such as Afghanistan or Iraq, where security remains fragile and there is ongoing conflict. The Brics, by contrast, represent an entirely different risk profile. Information and case studies abound, and the risks are well documented and, he says, well manageable:

“They are a natural starting point for any company that’s looking to globalise.”

A challenging environment

Manageable or not, though, the risks are certainly still real.

For a start, the recovery brings its own challenges. In China, for instance, the return to growth is seeing upward pressure on wages. The resurgence of the labour-intensive export sector has seen minimum wage hikes in the range of 15 to 25% in a couple of coastal provinces already this year, says Xianfang, and it’s something foreign companies need to keep an eye on: “It’s a pretty big jump.”

And that comes on top of new labour laws right at the start of last year increasing the welfare provisions foreign firms had to put in place for workers. This caught many out, led to a surge in lawsuits and continues to be an issue.

Perhaps more to the point, says Jardine Lloyd Thompson’s head of political risk analysis, Elizabeth Stephens, even if the worst fears of the crisis didn’t materialise, it still did nothing to improve things.

“I’d say every challenge of operating in emerging markets was exacerbated,” she says. “Certainly nothing became easier.” And that means the traditional risks remain – and remain substantial.

Perhaps most high profile, given last month’s attacks in Russia, is terrorism, and indeed it is a factor in others among the Brics, most notably in India, where terrorists have both the capability and intent to stage attacks. As Rachel Shoemaker, head of Asia Forecasting at political risks firm Exclusive Analysis, puts it, it is not if there is going to be another terrorist attack, but when and where.

However, it is also possible to overstate the risk for international businesses. In China, for instance, most of the terrorism is restricted to the Xinjiang province in the west – not the focus of most foreign investors. In Russia, meanwhile, while private sector employees were caught up – and killed – in the attacks, they have been aimed at The Federal Security Service and other symbols of government authority, not foreign companies. The likelihood insurgents would target foreign businesses is low, with the exception of those in the energy sector, since Siberian groups have threatened to target strategically important infrastructure.

Of greater everyday consequence for most companies, however, are the persistent bureaucracy, corruption and government interference that are, to a greater or lesser extent, factors in all the Brics.

In Brazil both federal and local government are increasingly cracking down on fraud and tax avoidance. However, one of its principle impacts has been to highlight the incoherence and contradictions in the proliferation of municipal, state and federal regulations. “They are closing the loopholes making it harder for people to escape but in doing so they are actually exposing some of the weaknesses of the system,” says Keith Martin, director of international trade and investment at Aon Brazil.

It’s a similar story in India, where the benefits of a reasonably stable democracy and the rule of law remain offset by a painfully slow judicial system and overwhelming bureaucracy.

Meanwhile, the crisis undoubtedly increased corruption in both countries. Brazil again provides the most graphic example, with the recent kick-back scandal in its capital Brasilia: videos showing a newspaper editor stuffing his underwear with bank notes and law makers forming a prayer circle to thank God for their bribes became Youtube sensations last December. So widespread is the alleged corruption, says Martin, that questions are being asked about effectively putting the state government into receivership.

And Brazil is possibly the best of the Brics. Corruption is more of an issue in China, where it would be wrong to read too much into the recent Rio Tinto case; bribes are still widely tolerated, and it can be almost impossible to do business in some areas without them, says Shoemaker. Even in the big cities such as Shanghai and Beijing it remains endemic in certain industries, such as construction.

Nevertheless, it is still worth sticking to the law, reckon analysts, and not just to avoid the possibility of criminal charges.

“We tend to find that not only is it ethically unsound but it doesn't really make sense from a business perspective to operate on the basis of bribes,” says Denison. “Otherwise, it’s pretty much like giving a lump of meat to a Rottweiler; they’ll gobble it down and immediately ask for more.”

The Bircs?

It is Russia, though, that probably poses the greatest challenge in terms of both corruption and the threat of government interference.

Take corruption, first. Most of the other Brics are roughly middle ranking. In Transparency International’s 2009 Corruption Perceptions Index, Brazil was ranked 75th, India at 84 and China at 79. Russia came in at 146, out of 180 – equally placed with Kenya, Sierra Leone and Zimbabwe, amongst others.

Similarly, the threat of government interference in Russia remains high since an independent legal and regulatory framework is largely absent. The gravest risk to foreign investors, reckons Stephens, is having a contract renegotiated. “The rule of law doesn't quite operate in Russia, which can make it a bit precarious for investors, particularly in any sector that is seen as strategic,” she notes.

In fact, according to Professor Ephraim Clark, professor of finance at Middlesex University and founder of Countrymetrics, which provides political risk analysis tools, it is factors such as these that make Russia – and also China – so difficult for Western businesses. In Brazil and India the rule of law and democratic structures more or less prevail, he says; in Russia and China, the environment businesses encounter can verge on the “surreal”.

“They wouldn’t be where I would look first,” he says. “It would be Brazil and India, and then Russia and China – I’d rename them the Bircs.”

Others would be tempted to go further, and argue that Russia is flattered by being placed among the other Brics at all. It was, for example, the only one to be hit hard by the recession, with GDP slumping 7.9 per cent – a reflection of its dependence on oil and gas exports, and while it has since bounced back it remains questionable whether it will live up to the optimistic forecast its inclusion in the Brics suggests.

The Central and Eastern Europe Business Centre of PricewaterhouseCoopers recently predicted that Russia could be the largest European economy in 2020, but it equally may not, admits partner Alex Bertolotti. “With Russia,” he says, “it is often one step forward, half a step back.

“It is sometimes its own worst enemy.”

Certainly there are other strong contenders for its place among the developing world leaders. Consider South Africa, for example, the most powerful economy in Africa, and this year expecting a boost from the World Cup. For some, the best reason for keeping it out of the Brics is that it is simply better considered as a developed nation. Although power outages remain a serious issue and the murder of white supremacist leader Eugene Terre'Blanche has highlighted continuing social tensions, it has an educated work force, the rule of law and good communication infrastructure. In January, Aon’s annual Political Risks Map also downgraded its risk level.

“That’s why its currency is so strong – outperforming the Real and Australian Dollar,” argues Andrew Barr-Sim, managing director of Drum Resources, a commodity supply chain specialist in Durban. “The international markets are already treating it as a developed commodity-based country.” Russia, by contrast, he says, is “one of the most corrupt countries on earth”.

Not everyone would agree with the comparison but it does illustrate that it’s difficult to draw too many conclusions about the countries from their inclusion in the Bric grouping. As another academic, Peter Enderwick, professor at Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand and author of Understanding Emerging Markets: China and India, puts it: “It might be a great shorthand for size and projections about overtaking developed economies, but it is not a useful basis for risk analysis.”

There is no shortcut for properly analysing individual countries and putting in place the structures and people to mitigate the risks.

Unfortunately, this is where Enderwick fears many are still falling short. Even if they assess the political and traditional risks, they fail to take account of the difference in culture and put in place adequate controls. The New Zealand dairy firm caught up in the Chinese melamine scandal in 2008 was a good example, he says. “It had just three people in its joint-venture partnership with China. Only two of them spoke Chinese and one of them was based in Hong Kong. Are we surprised there were problems?”

As he puts it: “You can’t work with a local partner and just assume that everything operates in the same way. It doesn’t, and companies have too often been unwilling or unable to see the differences.”

Postscript

Peter Davy is a freelance writer