After the political shocks of 2011, French risk experts consider that 2012 is likely to be equally challenging. Political risk takes many forms, and risk managers need to be on their guard

“Our people were shocked.” This was the reaction of Orange’s Egyptian employees on finding out that the mobile network was being shut down on government orders, right in the middle of the defining moments of the Arab Spring. But, such is life, says Alain Hocquet, risk manager at Orange. There is nothing a risk manager could do to stop it.

Political risk looms ever larger in the consciousness of risk managers. With opportunities for growth within Europe stagnant or declining, large companies need to look elsewhere. And this means, says Stanislas Chapron of Marsh, they are forced to contemplate regions of the planet which carry increased political risk.

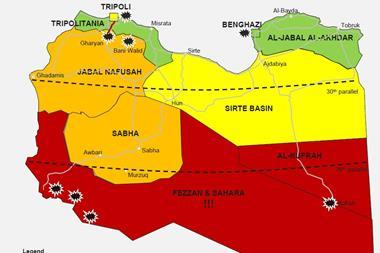

There are plenty of political developments to cause concern for the risk manager contemplating 2012. Iran looms large. Here is a messianic regime, given to talking of expunging Israel, and widely suspected of working to achieve the nuclear means to bring this about. Elsewhere in the region, the convulsions of the Arab Spring have yet to play themselves out. Syria remains unresolved; Libya is hardly stable, nor is Egypt. What of Yemen? What of Lebanon, What, even, of Saudi Arabia?

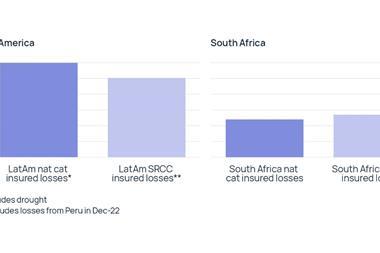

Much of Africa looks equally unpalatable, from the viewpoint of political risk. JLT’s World Risk review is headlined ‘Nigerian instability delivers stark warning to Investors’. The ongoing conflict in Somalia shows no sign of dying away, while the problems of piracy caused by that failed state continue to affect maritime trade throughout the Indian Ocean. Meanwhile, the hostile rhetoric emerging from the ANC Youth League in South Africa has served to raise concern among potential investors.

“2012 is going to be a challenging year,” says Julien Artero, Senior business development manager at Control Risks. “There were many new developments in 2011, which may have further to go. We must wait to see how things settle down.” He notes that there has been an increase in security risks in regions which used to be safe, which presents a challenge for investors. He also cites the growing awareness of the need for corporate integrity in the face of bribery and corruption as being an issue. “Many companies are coming to realise that they may be exposed, and are seeking advice.”

Stanislas Chapron echoes the perception that 2012 will be a challenge.

For French companies with historical links to North Africa, he thinks the political risk is somewhat alleviated by ingrained knowledge.

Where companies have no links, no direct knowledge, and must work on the advice of others, the situation is more difficult. It is, he says, a risk in itself. His advice? “Risk managers must have open views and be prepared for anything.” He commends keeping a close eye on the markets. “Often you can feel the little winds there – the ripples – before the big storm arrives. Be aware.”

But, as Alain Hocquet of Orange reflects, political risk is not always as obvious as it might seem at first sight. Orange, as he points out, operates in Equatorial Guinea, which measures on most scales as the second or third most corrupt country on the planet. On the traditional risk map, the probability of something going wrong in such a country is high, yet the impact on the group as a whole would be small. In a country such as France on the other hand, the probability might be very low, but the impact would be very high indeed. Which should be the more important in the minds of shareholders, and indeed in the mind of the risk manager?

For a mobile telecoms operator, such as Orange, the risk of intervention by governments is always high, as telecoms operations are effectively subject to a license – which can be given or withdrawn, and often comes with clauses concerning public security, co-operation with law enforcement, and so on. Hocquet points out that it is the use some governments may make of such clauses that can cause problems. The clauses are not in themselves illegitimate . Indeed, during the world cup in France, there were arrangements to selectively monitor the networks to prevent civil disorder being caused by hooligans. “The problem,” he says, “is that some people in the field of corporate social responsibility expect companies to be better than the states they operate in. They forget that to operate in a country, you have to accept the rules. Even in the face of possible arbitrary decisions, providing people with access to modern telecommunications is still the better choice.”

Nor is political risk confined to one manifestation. It has many different faces, of which arbitrary taxation is one. “It is more common, pervasive and invasive than any other,” says Hocquet.

“Governments all over the world consider telecoms operators as a cash cow.” Telecoms operators are not alone. The oil industry is another popular target for governments in search of easy money, as was seen in March 2011, when the UK government raided the North Sea oil industry to the extent of a £2bn levy to pay for commitments elsewhere.

Political risk is always the great unknown. “Expanding our footprint is part of our strategy, and carries risks like any strategy,” says Hocquet. “You are buying something in a competitive environment, and you are expected to create value, and of course experience is a key condition for success. But political risk is a bit like buying a cat in a bag. You don’t know what it will be like.”

No comments yet