Flourishing interest from SMEs and a growing awareness of non-traditional risks spell good news for captive insurance

Managing a captive is a full-time job. The question for many captive owners is whether that should be their full-time job or somebody else’s.

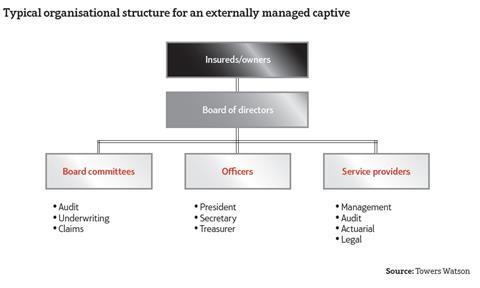

In simple terms, smaller parent companies tend to want to outsource the day-to-day running of their captive to a captive manager, recognising they lack the scale, capacity and knowhow to manage it themselves. From record-keeping through claims and underwriting analysis to preparing financial statements and issuing regulatory filings, many of these functions are not a core competence of the parent firm.

Here the common reasons for outsourcing to a service provider are clear. “It does not make sense to think about managing a captive yourself in-house unless it’s going to be of significant scale,” says Kane group chief executive Simon Hinshelwood. “It is unlikely to have the skills initially in-house. It might have complementary skills – financial and management, accounting,

company secretarial – but not in that particular area.

“If you want to self-manage a captive, you have to be large enough to warrant recruiting in or training up the level of skill that’s required,” he continues. “It’s just like any other outsourcing versus insourcing decision. If you’re smaller, it makes sense to outsource because that gives you economies of scale. Our trained accountants will work on multiple clients but if [a captive owner] has to recruit a trained accountant purely to work for them, then they’re bearing the entire cost of that.”

Size and skills

For large multinationals with well-established and diversified single parent captive companies, self-management might be a different proposition. “You reach a crossover point where because of size and diversity you need to have the skills there,” says Jonathan Groves, chief risk officer at Bermuda-based global insurer-owned reinsurer Equator Re.

“Those running particular risks that are unique and doing things that are particularly specialised would probably look to self-manage,” says Groves. “There is logic to doing it for some of the pharmaceutical companies, larger mutuals and financial institutions. In order to fulfil the regulatory requirements in terms of the frameworks and how you’re run on a day-to-day basis, you need to have skills and expertise in that company full time.”

Self-managed captives are, however, in the minority. It is estimated that only 4% of captives are self-managed. This in itself explains why captive management is such big business and why there are in excess of 40 captive managers around the globe, with the top five managers looking after more than 3,000 captives (around half of the total number of captives globally).

Size is not the only factor determining whether to insource or outsource. “There is a rough correlation between the size of the captive and the resource required to manage it, but other factors, such as the number of territories or the frequency of premium or claims flows, can also make a big difference,” says Tom Stephenson, a captive expert at Guernsey-based Robus. “There are some relatively small captives that require a great deal of management.”

“Captives that insure customer risks, for example, can have more frequent premium flows, more regulatory requirements and more day-to-day underwriting management than a large captive with first-party-only risk in one territory with one renewal date,” he adds.

A cultural imperative

The most common reason cited for opting for a self-managed captive is that it offers greater control and more oversight. “For some organisations, managing the captive in-house is a cultural imperative,” says Stephenson. “It’s just how they do things. The other potential advantage is that resource is more efficiently used. By employing a captive manager, you could be doubling up on resource, when other parts of the group have the capacity and skills to take on certain captive management tasks.”

“At Robus, we recognise that not all captive owners want to be fully managed or fully self-managed,” he adds. “A captive may employ its own staff or other parts of the parent group may undertake certain functions such as preparing management accounts. In cases such as these, we essentially fill in the gaps.”

Of course, when opting for the self-managed route, it helps to have the captive located near the parent company to ease access and communication. With its Netherlands-based captive Roeminck close to home, parent company Heineken is slowly moving towards a structure that involves more self-management.

“The reason why we are moving it step by step towards managing it ourselves is simply the speed of communication,” says Heineken International group insurance manager Eric Bloem. “The process goes faster and it’s simpler to oversee what is happening. That’s why we’re moving to insourcing and moving away from outsourcing – it will help to optimise communication and enable us to make faster decisions.”

Many smaller captives are also newer captives, so the process of self-insurance is also a relatively new one. Over time they grow, gain all-important scale and diversification and at that stage could look to get more involved.

“If you leave quality out of the equation, it’s only about cost and efficiencies,” says Bloem. “You can do it by yourself in the correct manner, or a consultant can do it: it’s a matter of choice. Once captives become more mature, they’ll slowly shift to doing it themselves. The biggest captives in the world are 100% self-managed and the smaller captives lean heavily on the consultants, as we did in our early years.”

Regulatory compliance

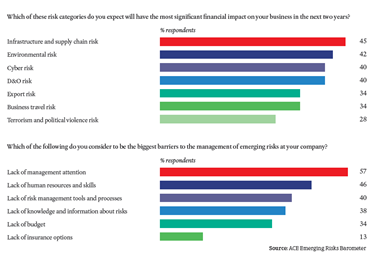

One of the biggest challenges is contending with Solvency II, Europe’s new regulatory regime for the (re)insurance industry. When it comes into force on 1 January 2016, it will have a big effect on how EU-based captives are managed and the kind of resources that need to be brought in house should self-management be the longer-term solution.

“As a big insured we recognise that Solvency II is a good thing for the insurance industry, so as a client of the insurance industry we appreciate all this,” says Bloem. “But as a captive manager you are confronted with many elements that are not adding value for the captive.”

Under Solvency II, there is the own risk and solvency assessment (ORSA), which comes under Pillar 2. Calculating the ORSA should incorporate the information provided by the actuarial function on the validation of technical provisions. “Captives do not employ actuaries,” says Bloem. “But now, owing to the regulations, you either have to employ actuaries or use the consultants. Most captives will use the consultants.”

Self-management also makes sense when the parent company already has a good insight into the insurance and reinsurance business and also has the resources it needs in-house to fulfil the role. Groves sees obvious synergies between the two.

“As part of an insurance company, we already have a lot of those core skills, or if we need to we can access them to help influence and shape our decisions,” he says. “However, insurance accounting and filing with the regulators is not part of your core competencies if you’re a manufacturer, but as an insurer and reinsurer, it is one of our core competencies and therefore [a captive manager] is not going to provide anything over and above what we can do ourselves.

“In today’s environment you have a variety of different demands on you as an owner and an operator,” he adds. “If this isn’t your core business and you’re not that large, there’s a logic to using the everyday expertise of a manager in supporting and servicing you, providing you with a range of services that work and suit where you are. On the other end of the scale we find there’s no practical benefit in using a manager. Because of the range of what we’re doing, no one manager can cover off all the needs we have.”

Captive managers

Independent or broker-owned: what’s the difference?

“I genuinely don’t believe there is any difference – at the end of the day, you’re looking for the expertise. You do see examples where an independent manager has gone above and beyond, but I would argue that it’s more likely to be the individual than the company.”

Jonathan Groves, Equator Re

“The independent captive manager has no obvious potential perceived or real conflict of interest in advising the captive owner, because no part of its business is going to earn a big brokerage fee for doing so.”

Simon Hinshelwood, Kane

“There’s no advantage and that’s simply because of the structure of the broker with which we work. It has an efficient Chinese wall between both organisations and we can only compliment it for that.”

Eric Bloem, Roeminck

“Independents, typically being small- to medium-sized businesses, have a more entrepreneurial or commercially minded attitude… Broker-owned managers can be competent but passive and bureaucratic”

Tom Stephenson, Robus

No comments yet