Case study demonstrates how exposed supply chains are to interconnectedness

When the container ship Svendborg Maersk was surprised by a violent storm in the Bay of Biscay in February 2014, it was suddenly pitched by ten-metre waves. As the vessel rolled violently from side to side, at one point nearly turning turtle, hundreds of containers were washed overboard.

When the ship finally made port and the crew was able to do a tally, more than 500 containers had been lost and another 250 damaged. It was the largest container loss in Maersk Line’s history running to more than $10m.

The incident provides a telling illustration of how vulnerable the shipping, ports and oil giant is to extreme weather. “As one of the most asset-heavy companies in the world, we have a lot of steel out there – platforms, drilling rigs and ships exposed to sea and heavy weather,” says Lars Henneberg, head of risk management for Maersk Group.

Exposed supply chains

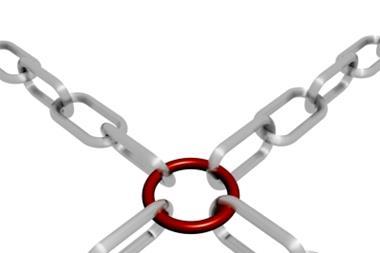

The incident also demonstrates how exposed supply chains in general are to risks that go far beyond the elements. Not so long ago most logistics companies, big and small, considered physical losses, usually from adverse weather, as the main risk but now, as supply chains become longer and more complex, they are increasingly hostage to a much broader array of dangers that threaten not just physical goods but the company’s reputation, business continuity, its personnel, and even its presence in countries as political violence makes an unexpected and unwelcome reappearance.

The world’s oceans are the most vital artery for the transport of the world’s trade. More than 90% of manufactured goods and produce are carried by sea, and in the last 40 years the volume of seaborne trade has quadrupled, according to the International Chamber of Shipping.

Meantime trade by the other main arteries – road and air – is growing at a similar pace in an unstoppable process that is creating increasingly interdependent risks. Airborne cargo grew by 4% last year, according to IATA.

The implications of this headlong growth are profound.

“The discipline of risk management has become more complex and diverse than ever,” say Andrew Gray and Michael Leibrock, respectively group chief risk officer and chief systemic risk officer at US-based DDTC, an authority on corporate and especially financial stability. “[This] is driven in large part by new regulatory mandates, an explosion of technological and financial innovation, and the growing interconnectedness of global markets.”

As they explain in a recent paper, today’s risk managers must now analyse, measure and quantify the impacts of an expanding range of risk categories such as operational, systemic, technology, vendor, business continuity and physical risk. Although they refer essentially to the financial sector, their observations apply equally to any company with cross-border activities.

Some of these risks are perforce of a company’s own making as they step into new territories.

“This evolution of risk management is essential because firms need to have a deeper understanding of all aspects of the risks they face as well as the intricate spider’s web of interconnections they create,” say the authors.

Off the radar

The latest World Economic Forum’s survey of the ten global risks of greatest concern includes four that were probably off the radar of logistics groups until a few years ago. All four of these are environmental – water crisis, failures in managing climate change, rising incidents of extreme weather events, and food crisis.

If three of these sound remote to ship captains, pilots and truckers, the people managing their companies see them as direct threats.

Nearly half of chief executives agree that resource scarcity and climate change will transform their business, according to the latest PwC Global CEO Survey.

And right on cue, EU environmental laws now penalise firms that cause damage to “animals, plants, natural habitats and water resources, and to the land”. The scope of these liabilities was extended to include offshore oil and gas exploration and production after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon incident that has cost BP $42bn, and still rising.

Thus, in an increasingly interconnected world, risks are cascading downwards from a ‘parent incident’ such as the 2011 floods in Thailand that cost $26.5bn in lost economic opportunities, as well as spreading outwards in a new era of interconnected risk – the so-called ‘spider’s web’.

Risk managers may be able to do little or nothing about the risks themselves, but they have to manage them, such as the re-emerging one of political instability as we’ve seen in the Middle East since the Arab uprising and in Eastern Europe in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Crimea. “We all have to go where potential business is and very often this is in difficult countries,” explains Jo Willaert, corporate risk manager at imaging solutions manufacturer AGFA. “ The role of risk management is to support the decision making process.”

Rethink

It was incidents such as the near sinking of the Svendborg Maersk that prompted the company to re-think its risk management processes from top to bottom in a way that takes into account the interconnectedness of the threats the company, which employs 80,000 people in 130 countries, faces.

The immediate trigger for the top-down re-think came after an incident in February 2011 when the floating production platform Gryphon broke loose from its anchors in the North Sea and was swept 180 metres off-station with more than 100 workers aboard. The result was an insurance payout of nearly $1bn, one of the biggest-ever in the energy sector at the time. Following the Svenborg and Gryphon events, Maersk decided to rely less on insurance and more on self-help to confront its multiplicity of threats.

“Insurance is not the solution to protecting our assets,” Henneberg told the company’s inhouse magazine. “We need to do something about our losses and not let others pay for them. It is a change in mindset. Today we focus less on risk transfer or buying insurance and more on risk improvement. This means loss prevention activities, assessing our exposure to certain risks and how prepared we are for when things do go wrong.”

Thus Maersk is in the middle of a long-running sustainable risk management programme. Each year it focuses on a particular risk such as the security of oil assets in West Africa, the threat of piracy, and the new mega-vessels entering Maersk Lines fleet.

Perhaps more importantly, every event triggers a bout of hard-headed analysis. Since the Svendborg Maersk incident, for example, in the event of a Force Nine forecast it is mandatory for all vessels to alter course from the storm or remain in harbour. Sometimes the best form of risk management is not to take any.

No comments yet