What will it take to make sure companies protect the data they hold?

This year in the UK there were almost three hundred reported data breaches. That is a staggering amount of sensitive information that could be in the wrong hands.

Britain’s Information Commissioner revealed that there have been 277 instances where the authorities have been informed about a potential data breach. All this has occurred since November 2007 when the Government itself lost 25m child benefit records.

What will it take to stem this tide of sloppy information handling?

The threat of enforcement action doesn’t seem to have done much. In August, the UK’s privacy watchdog was given powers to fine offending companies. Parliament hoped this would act as a deterrent to ensure organisations take their data protection obligations seriously. But independent research has shown that organisations are still more worried about the damage to their reputation resulting from a data breach, rather than regulators fining them.

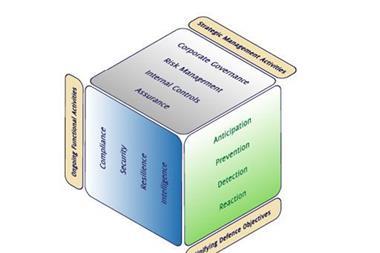

Some say it’s a question of rethinking old-fashioned ideas about security. According to the government statistics the most common reason why data goes missing is because of the loss of removable media, such as a laptop or memory stick. Yet many security strategies are still focused on protecting the network from outside attacks.

The privacy watchdog believes the answer lies in making senior management personally responsible for the safety of the data their organisations hold. ‘CEOs must make sure that their organisations have the right policies and procedures in place,’ said Richard Thomas, the UK’s Information Commissioner.

It’s clear that senior management needs to make sure these policies are driven into the culture of the organisation. ‘The most important and effective security project that a company can undertake is the creation of a corporate culture that is centred on security,’ said Gordon Rapkin, chief executive of data security management specialist, Protegrity.

The Information Commission acknowledged that there were probably many more un-reported security breaches than the statistics themselves revealed. At the moment in the UK there is no imperative for a private company to inform the government if it loses confidential information—although the public sector is compelled to do so.

Many believe mandatory reporting, as is done in the US, could provide a strong incentive for companies to clean up their act. But, while supranational associations have called on European states to introduce similar legislation, at this stage the UK appears to be sceptical about placing a statutory duty on organisations to notify people whenever a breach occurs. ‘Each breach carries different levels of risk and, consequently, requires a different response,’ said Thomas.

No comments yet