In a media-savvy world, hard won reputations are easily lost, particularly over environmental scandals. Companies must take action now to put safeguarding procedures in place

Part of an environmental risk series supported by

No one can eliminate bad luck, and disasters can hit even the most careful firms with the best risk management policies. However, the extent to which these events go on to affect a company’s reputation – and its bottom line – is down to a company’s risk management procedures.

“It is essential for a business to demonstrate to the public that it is prepared to deal with the situation, take charge and protect anyone affected, whether they are customers, stakeholders or employees,” says Shane Russell, malicious product tampering specialist at Red24assist.

The list of firms that have suffered from severe brand damage after an environmental crisis, either as a result of their own operations or those within their supply chain, is long. Safeguarding a brand depends on a proactive approach.

People are predisposed to assume the worst – that companies prioritise making money even at the expense of the environment. And businesses must stay one step ahead to avoid that mindset establishing itself. This is nothing new. But what has changed is that the level of awareness of environmental issues has risen enormously over the past couple of decades, with the millennial generation leading the way, as has the means by which these concerns are communicated.

“The biggest challenge is social media and the fact that it is so easy to lose control,” says Russell. “You cannot change what people post or when.”

Carl Leeman, chief risk officer at Katoen Natie, says: “When it comes to reputation, one golden rule will always prevail: in these times of ultra-fast communications and electronic media, it is not a good idea to try to hide something.

“Following an incident, if a company comes out with a message first, they are putting themselves in a position where they can control the message and the information. This way, they stay one step ahead of the pack.”

Now more than ever, it makes a big difference to have a crisis management plan (CMT) in place. “In the old days, a firm might get a call from a newspaper asking for a comment by a certain time of day, so they had time to prepare,” says Russell. “Now companies have to provide a more instant response – they have no time. Companies now need a media strategy.”

Companies must be sure of how they will communicate – will they upload information to their website and how will they use Twitter? They have to be ready at a press of a button.

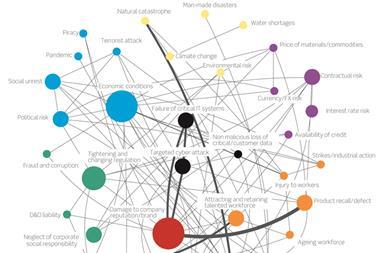

Russell adds: “Companies have to know in advance what their risks are and, although they cannot cover every eventuality, they can cover most. Think about the worst case scenario.”

Supply chain management needs to be part of a firm’s risk assessment. The longer it is, the more checks firms have to make. “The horsemeat scandal was a real wake-up call in this respect because it showed how complex supply chains had become and how many firms were unsure of the stages their products had gone through before they arrived on the shop floor.

“I have known firms go out of business over these kinds of claims, particularly if they are one-product firms.”

Companies have to take action and be seen to take action, urges Russell. “The public is much quicker to hold companies to account over their actions. The days are long gone when [an incident] might never hit the media and you might just get away with it.”

THE INSURANCE SOLUTION

Managing the reputation of a business in a crisis can be expensive – and the right insurance can make a huge difference.

“The markets have begun to realise in recent years that reputation is a very important aspect of any loss,” says Willis environmental practice leader Richard Sheldon. “It always was to an extent, but there was not necessarily the cover available, and that is what has changed.

“Reputational coverage has only been around for the past few years but it is starting to work pretty nicely… It is a great way to transfer some of the risk and really does bring value to the table.”

This is particularly so, given how complicated some environmental claims can be. With groundwork spills, for instance, there may be a co-mingling of contaminants from different companies within industrialised zones, and it may take time to work out who is responsible for what. “You need to be out in front while that’s happening,” says Sheldon.

“In response, we are seeing more firms that might not necessarily have been regulated or contractually obliged to have cover, but want it because they see it as a good thing to have. A case can now be made for almost any class of business to have some environmental exposure that is not covered by the property/casualty policy – particularly in cases of liability if, say, a pollutant migrates onto your property from a neighbour’s property.”

Downloads

sr ace environment final

PDF, Size 22.07 mb

No comments yet