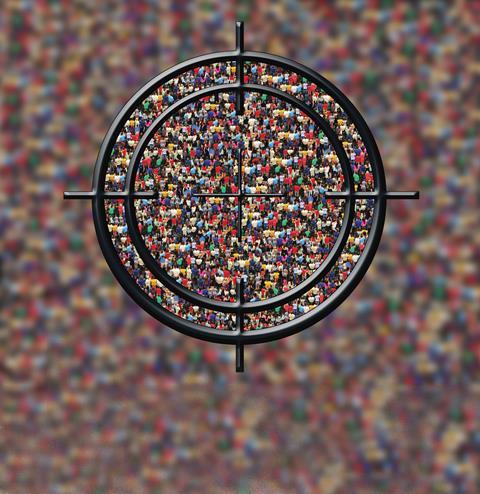

Murderous jihadists aren’t the only terrorist threat. Militants on the left and the right are turning to violence too

Islamist terrorists targeted several European cities in the past year, including Paris, Berlin, Stockholm, Manchester, London and most recently Barcelona.

Meanwhile across the globe, the threat environment has shifted towards less sophisticated but less predictable attacks by homegrown jihadists. Nearly all of them are motivated by sympathy or affinity with Islamic State (IS), and responsiveness to online propaganda and outreach efforts.

“These so-called remote-controlled individuals have been coached, encouraged and guided in terms of conducting attacks,” notes Matt Henman, head of Jane’s Terrorism and Insurgency Centre (JTIC) at IHS Markit. “We’ve seen a lot of recent attacks, particularly in Western Europe, where individuals had contact over encrypted messaging channels; where they are guided by key individuals from that country who have that homegrown knowledge about how they should be attacking, who they should be attacking, timings, etc, which ensures that in each country they are striking targets which have maximum resonance and impact. The London Bridge and Manchester attacks, for example, were both carefully calculated to cause maximum impact and maximum outrage, exactly IS’s primary goal.”

However, while Islamic militant groups are grabbing the headlines, the re-emergence and radicalisation of extremist groups on the right and the left – encouraged by political polarisation – is also of concern. Jonathan Wood, director of global risk analysis at Control Risks, says: “While left-wing groups remain relatively contained, violent attacks attributed to right-wing extremists have increased significantly since 2015. The threat from right-wing extremists in Europe appears to be increasing, with some recent threats shifting targets and tactics to lethal attacks on government officials.”

Globally, the number of riots and protests has increased. Srdjan Todorovic, head of terrorism at Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty (AGCS), says: “Following the Arab Spring, there has been an increase in populism and political activism, meaning that people are more willing to hit the streets and protest against the things they feel hard done by or object to. There are lots of examples, such as Turkey or Venezuela – even closer to home, in Germany, when US president Donald Trump visited during the G20 summit in Hamburg in July. There are always some G20 protests, but a few years ago it would not have been to the same extent that Hamburg was.”

The attacks and riots in Hamburg highlighted the co-ordinated, transnational movement of organised anarchist and left-wing groups who are dedicated to attacking Western and transnational symbols of capitalism and globalisation.

Henman points out that in terms of frequency of violence and the threat to the commercial sector, left-wing anarchist violence should be a bigger concern for businesses. Left-wing terrorists are much more focused on property damage and damaging infrastructure than Islamist terrorists, who are primarily concerned with causing as many casualties as possible.

Two extremes

At the moment, left-wing violence in Western Europe is typically limited to minor property damage, such as bricks through the window, although countries such as Greece have seen a resurgence in anarchist violence since the financial crisis.

Henman notes: “It wouldn’t take a tremendous shift for the patterns and intensity of anarchist and left-wing violence to develop further and move towards Western Europe. It’s not a trend we’re seeing at the moment, but it’s something to be aware of.”

On the other side of the spectrum, violence organised and co-ordinated by right-wing extremist groups is increasing and intensifying, particularly in the UK, France and Germany, Henman says. “They are typically focused on attacks on individuals, companies or institutions who they perceive to be ‘race-traitors’, so people who are supportive of or assisting in the resettling of refugees and migrants. In Germany, there have been a stream of small arms, arson and explosive device attacks targeting facilities used to temporarily house refugees.”

Furthermore, in these countries an attack by militant Islamists is often quickly followed by a spate of low-level retaliatory or reprisal violence by right-wing extremists.

“These types of attacks feed into the ideologies of both, to the extent that it undermines the idea of a cohesive, integrated multicultural nation,” Henman explains. “They are beneficial for both the Islamic State and right-wing extremists, because both want to portray their community as under threat, as being the victim of a violent opposing culture which doesn’t want to either accept or assimilate with them. So it’s a dangerous cycle that has the potential to escalate further and further.”

Despite the rise in terrorist attacks in recent years, direct threats and attacks against commercial assets remain uncommon in most countries.

However, terrorist incidents may have an indirect impact on business as a result of disruption in a city centre (including through lockdowns and cordons), or incidentally to employees caught up in an incident in a public space.

For businesses, terrorism risk is therefore mainly related to business interruption and people risk. To minimise the risk of being affected by a possible terrorist incident, businesses are reviewing their existing policies, procedures, and threat and risk assessment, Wood says. “This may include adding scenarios around attacks in public spaces, or coping with business disruption as a result of an attack.”

He also sees more companies providing training and reassurance to employees, both in advance of incidents and in the wake of an incident. In particular, this has recently included an emphasis on ‘active shooter’ or ‘active assailant’ training, including in Western European countries.

Knock-on effects

Steve Ryan, consultant at JTIC at IHS Markit, adds: “The important part of mitigating risk is understanding your vulnerabilities. There’s a range of risks for organisations, but crucially it depends on what the organisation does and whether they are going to be the primary target, or whether they are going to be impacted as a secondary effect of an incident.

“There are organisations that don’t feel they’re vulnerable to a terrorist attack, because they don’t think they’re going to be targeted. These are the ones that fit into that second category of being affected as a secondary effect.

“An example of this is if the tube system in central London were to shut down because of an incident and they have employees who are either trapped underground or who can’t get into work.”

How insurers are adapting

Following the recent terrorist attacks in Western Europe, the insurance industry is updating and improving certain products, such as terrorism liability. “Insureds have an obligation to the customers or visitors to a certain place, therefore if something happens to them whilst at the premises, a question of negligence arises. That’s one cover we’ve seen a growth in, or certainly a growth of interest and enquiries in,” says AGCS’s Todorovic. Clients are also increasingly interested in non-damage business interruption cover, he adds. “With the London Bridge and Borough Market attack, it was especially pertinent that there was no physical damage loss, but the area was shut down for two weeks for investigations, clear-up and other information-gathering. That was a significant business interruption loss. So the insureds are now requesting this type of cover, whereas before they were more focused on the physical damage, which leads to direct business interruption. Now we’re looking at non-damage business interruption and the market is striving to meet these needs.”

No comments yet