Oil rig disaster puts whole industry in deep water

No one has ever claimed that exploring for oil was without risk. In fact, a multitude of risks hovers over a drilling rig, like a cloud of harpies. The most prominent is the financial risk: the likelihood, expressed as ‘chance of success’ (COS), that a multimillion-dollar punt will end in a dry hole, a reservoir that doesn’t flow, or oil that does not exist in commercial quantites.

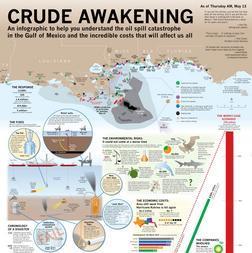

See our infographic depicting all the effects of the BP spill.

The COS in many cases can be estimated at 20% of even less. But oil companies take account of this and spread the risk as much as they can by farming out shares in the well to other interested organisations.

The next, and much more serious risk, comes from the act of poking a hole into a reservoir of an inflammable mix of compounds whose temperature and pressures are unknown – or that are estimates at best. But the drilling industry has been around long enough to have developed a variety of technologies to counter this risk.

Chief among these is to use a heavy lubricating mud in the well to hold down the pressurized hydrocarbons, and to cement the sides of the hole as it is drilled , in order to prevent the reservoir leaking into the sections already drilled. And the safety measure of last resort is the blow-out preventer. This structure of assorted hydraulic rams is designed to instantly cut off and seal the well if something goes wrong. It appears to be this that failed on the Deepwater Horizon rig in the Gulf of Mexico, allowing an expanding bubble of flammable gas to surge up the well, with fatal consequences when the gas ignited.

When something goes badly wrong, the money spent on drilling the well becomes a mere drop in the ocean compared to the costs involved in salvaging the disaster. Meanwhile, the next rank of risks – political, environmental and reputational – close in. And in the background, the inevitable regulatory risk begins to swell above the whole industry, driven by the understandable ‘never again’ reaction from those looking at the destruction of an environment or the ruination of a local industry.

Carrying the can

As the world’s insatiable demand for oil continues, drilling in deep offshore waters is increasingly common.

The Deepwater Horizon was drilling in 1,500 metres of water at the time of the explosion. The ruined well then started leaking oil – estimated at anywhere between 5,000 and 10,000 barrels per day, and at a depth where no human being can operate. At the time of writing, several solutions devised by BP to stop the leak had so far failed to work.

As is common in the oil exploration world, BP had leased the rig, while the blow-out preventer was manufactured and supplied by a third company. Yet, without doubt, BP is first in the firing line, with White House spokesman, Robert Gibbs emphasising that Washington would keep its “boot on the throat” of the company to ensure that it stepped up to its responsibilites. BP has not been helped by its previous record in the Gulf of Mexico, with the 2005 explosion at the Texas City refinery still at the front of people’s minds.

BP chief executive Tony Hayward has been doing everything possible to shore up his company’s reputation. Early on, he accepted the company’s responsibility for the clean-up, said it would pay compensation in legitimate claims, and, according to the Daily Telegraph, has been touring US television studios to put forward BP’s case. But this may not be enough. As the inhabitants of the Louisiana coast contemplate the possible ruin of the fishing and tourism industries, the class action lawsuits are coming forward.

Meanwhile the environmental lobby is making the link, not just to the 2006 oil leak from the Alaska pipeline, but to BP’s involvement in the controversial Alberta tar sands project. For a company that had worked hard to turn around out-of-date working practices inherited from its previous leadership, and to be at the cutting edge of the exploration industry, it is a hugely damaging blow. The company’s slogan ‘Beyond Petroleum’ is already being warped on the internet to ‘Beyond Prudence’ and ‘Biodiversity Perishes’.

Industry setback

The further risk is to the industry as a whole. As recently as 31 March this year, president Obama’s administration announced the intention to open up oil exploration in offshore areas of the USA that had previously been off limits. They included the eastern Gulf of Mexico and the Arctic Ocean. Now that is potentially at risk.

At the end of April, Florida senator Bill Nelson wrote to the president: “It’s unclear whether any additional shut-off controls would have made a difference in this case. But the questions about the practices of the oil industry raised in the wake of this still-unfolding incident require that you postpone indefinitely plans for expanded offshore oil drilling operations.”

On 4 May, California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger renounced his intention to allow offshore drilling in the state. The Daily News reported him as saying: “You turn on the television and see this enormous disaster, and you say to yourself: ‘Why would we want to take on that kind of risk?’”

If the Deepwater Horizon leak lasts another month, it may come to rival the Exxon Valdez disaster, which spilled 250,000 barrels of crude onto the Alaskan coastline. The risk to the oil exploration industry could far exceed the damage done to BP’s reputation.

No comments yet